追溯

对着电脑打字的时候时常会有幻觉,但不得不承认是故意营造的。

有时半合着眼,低声屏气,像是蜷缩在城市角落的没落旅人,

数着千万驶过面前的大衣下摆,配上鞋底的踢踏之声,发难怪叫几声:世人皆负我。

此种时候除了我,世上只有他们,灰色的整齐划一的队伍,盲人的军列。

此时还总以为自己像个智者,先知,悲天悯人地感叹,不知者无罪,我原谅你们。

更具体的说法就是想趴在透明的天花板上,脸贴着玻璃,置身事外地点评一下见不惯的人物。

剩余的时候,心底就像冲洗照片一样渐渐显现出几张脸,不一定认识,但都是多年老友,

于是泡茶迎客,围炉夜话,看清了自己斤两,说些生活实事琐事烦心事新鲜事,

说不定一人自娱就着花生瓜子从黄昏侃到天际发白。此种心态下,整个世界特别可亲,

恨不得逮到路边等绿灯的大妈紧紧拥抱一下。

大街上四处奔走访友的都是我们,从脸蛋红扑扑的孩子到白发皑皑的八旬老爷子。

每种精神状态都有利弊。

超然于现实的客观视觉让我看到的是人类的共性,

放逐了没有国度限制的灵魂,培养一切让人忍耐孤独的品质。

不执着,只有自由这一种信仰,

可是这风化的过程要从实体的痛楚中提取成熟所需的元素。

而脚踏实地的过小日子容易让我满足,感谢天蓝云白,感谢我是我感谢太阳是太阳,

不挑剔,学向日葵想光明看齐节节拔高。在世俗的菜香肉味中睡死。

可是带着油烟气的幸福是实在的,不需要放眼世界,着眼于小处,人性也不见得就会被尘敝了。

也罢,也罢。这种提笔只见自己肚脐眼的东西,我又写不下去了。

我刚刚从第一种状态调回第二种。

流水账模式启动。

今天找到不说过去几天以为失去了的东西。

偷乐。

浪费粮食可耻。

写字丑是不可宽恕的罪。

掌嘴。自己下手,轻点儿。

Tuesday, November 30, 2004

Monday, November 29, 2004

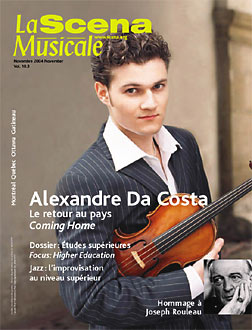

The possessed violinist: dearest Alexandre

Violinist Alexandre Da Costa is coming back to Canada this month for a number of concerts and the release of a new CD of works for solo violin. This recording -- his fifth with Disques XXI-21 -- gives us a chance to hear, in all its splendour, the Baumgartner Stradivarius loaned to him by the Canada Council for the Arts. The new release includes Bach's Sonata No. 1 and Ysaye's Sonata No. 2, as well as André Prévost's Improvisation and Robert Lafond's Solitario, the latter being the title of the CD.

Born in Montreal Canada in 1979, Alexandre showed an uncommon interest for both the violin and piano at a very early age. By the age of nine, he had the astounding ability to perform his first concerts with stunning virtuosity on both instruments, which brought him recognition as a musical prodigy. After having won several first prizes at the Canadian Music Competitions, his international music career took off with recitals and concerts in Canada and the U.S.

In 1998, at the age of 18, Alexandre received a Master’s degree in violin, Premier Prix Concours, from the Quebec Conservatory of Music where he studied with Johanne Arel. Concurrently, he also received a Bachelor’s degree in Piano Interpretation from the Faculty of Music of the University of Montreal where he studied with Nathalie Pepin and Claude Labelle. From 1998 to 2001, Alexandre studied with the violin master Zakhar Bron at the Escuela Superior de Musica Reina Sofia in Madrid.In the course of his studies, Alexandre also attended master classes and extensive courses in violin with several other internationally renowned figures, including Sergei Fatkouline, Christian Altenburger, David Cerone, Jose-Luis Garcia Asensio, Shlomo Mintz, Pinchas Zuckerman, Mauricia Fuks, Maxim Vengerov, Vadim Repin, Martin Beaver, Herman Krebbers, Robert Masters, Gerhard Schulz and Rainer Honeck.

Da Costa's persevering approach has earned him major recognition from the Canada Council for the Arts who rewarded him with a three-year loan of a magnificent violin--the Baumgartner Stradivarius of 1689. "It's a fabulous instrument!" says Da Costa. "It is helping my career on more than one level. I now get more attention from some conductors who wouldn't have thought of me before. My previous violin, an 1842 Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume, was also a very good instrument, and worth far more than I could afford. Each violin has its advantages and disadvantages. For example, the two instruments differ in power. Of course the Stradivarius is now my preferred instrument. I'll certainly feel a bit sad to have to give it back at the end of the three-year loan! Contrary to what you might think, it's not an easy instrument to play. In Vienna, where I live, some of my friends were curious and wanted to try it. They were really surprised to find it difficult."

Although audiences don't often think about the way instruments get passed around, it is a reality soloists at the start of their careers have to reckon with. "At first I said to myself, 'Wow! A violin worth three million dollars!' I treated it with extreme care, left it at home, and so on. But it's my working instrument and I have to have it with me at all times, in the street, the metro, the plane, or coming back to the hotel after a concert. I come from an artistic background: my mother is a painter and my father is in the theatre. It's not a milieu where there's a lot of money, and I would never have been able to pay for an instrument that would enable me to make a career in music. Therefore, I started with a modern Canadian violin provided by a foundation, and that's what I took to Europe. My teacher introduced me to a number of people and eventually I was able to get a superb Ruggieri for six months. It had belonged to Yan Kubelik. Then I was lent a Balestrieri. Following a concert in Montreal, a music-lover decided to help and bought the Vuillaume in order to lend it to me. Then I entered the competition for the Canada Council instrument bank, and here I am with a Stradivarius [and a Sartory bow, lent by the Canimex Foundation, which Da Costa uses with one of the 300 varieties of string provided by the Thomastik Company]. Things move quickly in the music world!"

[...]

Two days later, he will appear at a benefit concert at the Salle Claude-Champagne in Montreal marking the twenty-fifth anniversary of the music program at Pierre-Laporte High School... and its possible disappearance! The prospect touches a sensitive nerve in Da Costa. "It was my school! The proposed cuts are, in my humble opinion, a cultural disaster, and I'm committed to defending the program that enabled me to develop and gave me the time and the environment to do research and pursue artistic excellence. It would be very sad to see this unique program abandoned. To shut down a program that is open to all, whatever their financial status, will also confirm a false belief, which is that classical music is only for rich people. It's just the opposite, and I'm a perfect example of this. The Pierre-Laporte School is one of the organizations, along with the Conservatoire de Musique de Montréal, that allowed me to get a top-ranking musical education that was financially accessible."

Notes on the Stradivarius Violins

Antonio Stradivari was born in 1644, and established his shop in Cremona, Italy, where he remained active until his death in 1737. His interpretation of geometry and design for the violin has served as a conceptual model for violin makers for more than 250 years.

Stradivari also made harps, guitars, violas, and cellos--more than 1,100 instruments in all, by current estimate. About 650 of these instruments survive today. In addition, thousands of violins have been made in tribute to Stradivari, copying his model and bearing labels that read "Stradivarius." Therefore, the presence of a Stradivarius label in a violin has no bearing on whether the instrument is a genuine work of Stradivari himself.

The usual label, whether genuine or false, uses the Latin inscription Antonius Stradivarius Cremonensis Faciebat Anno [date]. This inscription indicates the maker (Antonio Stradivari), the town (Cremona), and "made in the year," followed by a date that is either printed or handwritten. Copies made after 1891 may also have a country of origin printed in English at the bottom of the label, such as "Made in Czechoslovakia," or simply "Germany." Such identification was required after 1891 by United States regulations on imported goods.

Thousands upon thousands of violins were made in the 19th century as inexpensive copies of the products of great Italian masters of the 17th and 18th centuries. Affixing a label with the master’s name was not intended to deceive the purchaser but rather to indicate the model around which an instrument was designed. At that time, the purchaser knew he was buying an inexpensive violin and accepted the label as a reference to its derivation. As people rediscover these instruments today, the knowledge of where they came from is lost, and the labels can be misleading.

A violin's authenticity (i.e., whether it is the product of the maker whose label or signature it bears) can only be determined through comparative study of design, model wood characteristics, and varnish texture. This expertise is gained through examination of hundreds or even thousands of instruments, and there is no substitute for an experienced eye.

Sunday, November 28, 2004

Saturday, November 27, 2004

what's between the ""

"看过一部默片. 其中有一个镜头,象一根细针一样击打着我的神经末梢:那里面的人在疯狂地舞动着手势,无序而混乱,都在竭力地表达着一些什么,却淹没在人潮中。这是一个孤独的时代,也许每个人都有一种表达的欲望,无声的或者有声的。都不希望自己的声音在人潮车流在淹没,希望有人能倾听自己内心的声音。"

Friday, November 26, 2004

Sonnet 130

MY mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red:

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damask’d, red and white, 5

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound: 10

I grant I never saw a goddess go,—

My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground:

And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare

As any she belied with false compare.

莎翁

英语老师说Sting有辑名唤Nothing like the sun.

今天上课听鸟叫,song thrush.

总共收录一百三十八种叫声的集子

我发现他还是个好玩的人。

____________________________________________________________________________

只要我还把钥匙挂在胸前,任何凶灵都不可以靠近我,我还是做我应该是的孩子。

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red:

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damask’d, red and white, 5

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound: 10

I grant I never saw a goddess go,—

My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground:

And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare

As any she belied with false compare.

莎翁

英语老师说Sting有辑名唤Nothing like the sun.

今天上课听鸟叫,song thrush.

总共收录一百三十八种叫声的集子

我发现他还是个好玩的人。

____________________________________________________________________________

只要我还把钥匙挂在胸前,任何凶灵都不可以靠近我,我还是做我应该是的孩子。

Tuesday, November 23, 2004

Monday, November 22, 2004

你只能活一次,好像,我不太肯定呢。

什么是生命?

我慢慢经历的一个奇妙的长大然后衰老的过程,像一朵雨后冒出的蘑菇。

一张没有目的地的火车票。

提供写作素材的仓库。

什么是亲情?

一团毛线,找不到开头和结尾,很温暖。

抓住你就再也不放手的猫。

生命交接仪式的祭司。

什么是友谊?

和其他蘑菇的相知相遇。

坚持,努力,诺言,兑现,支持,互助。

放手往后扑倒时相信有人会接住我。

崇高的感情。

浓淡皆相宜。

什么是爱情?

一个吃蘑菇的人。

没有光时的影子。

吊在憨驴脑袋瓜前的胡萝卜。

世界上为数不多的单方再怎么努力也不能成功的事。

听说不存在。

光荣的目标,说你相信它可以换来大白眼。

和其他温馨感情不同,涉及的人越少越好。

什么是理想?

太多了是贬义词,太少了还是贬义词。

永远待实现的一些想法。

如果实体化了就不叫理想了。

像

我要

大声说

我慢慢经历的一个奇妙的长大然后衰老的过程,像一朵雨后冒出的蘑菇。

一张没有目的地的火车票。

提供写作素材的仓库。

什么是亲情?

一团毛线,找不到开头和结尾,很温暖。

抓住你就再也不放手的猫。

生命交接仪式的祭司。

什么是友谊?

和其他蘑菇的相知相遇。

坚持,努力,诺言,兑现,支持,互助。

放手往后扑倒时相信有人会接住我。

崇高的感情。

浓淡皆相宜。

什么是爱情?

一个吃蘑菇的人。

没有光时的影子。

吊在憨驴脑袋瓜前的胡萝卜。

世界上为数不多的单方再怎么努力也不能成功的事。

听说不存在。

光荣的目标,说你相信它可以换来大白眼。

和其他温馨感情不同,涉及的人越少越好。

什么是理想?

太多了是贬义词,太少了还是贬义词。

永远待实现的一些想法。

如果实体化了就不叫理想了。

像

我要

大声说

Thursday, November 18, 2004

算命相面之说

信女彭丹 戊辰生人,個性趾高氣揚,希望在人群中突出自我,虛榮心重,熱衷名利,可得權貴,膝下有兒有女,但有刑沖,如屬女性,則個性溫婉,賢良淑德,但口直心快,服從丈夫。

前天写的

野草烧不尽,春风吹又生

现在几点: 20:47

你的全名: Dan Peng

你现在正在听谁的歌:The Zephyrs , When the sky comes down it comes down on you head,老是有几根弦噔~噔~地荡开

你在哪里读书(工作): 中不溜不破不算太不干净的PL,mtl,qc,ca

最后吃的一样东西是什么: 晚饭。。。自然是米饭,特殊一点的东西有木耳和香菇。

现在天气如何: 光脚踩着木地板会被冻伤

戴隐形眼睛吗: 不戴,怎么不问我戴不戴眼镜阿,这不问我就没有义务交待,你看我这态度也就知道了

上一次吹蜡烛的数目: 1

你通常吹熄这些蜡烛的日期: 星期一,化学有试验课

你们家养过什么:自残的松鼠,不会爬墙的藤,我

星座: 狮子

兄弟姐妹和他们的年龄: 没有

你有纹身吗: 没有,我耳洞都不敢有,怕感染

你喜欢你目前的生活吗: 还可以,有更多的时间可以用来看书就好了,如果老板补发他欠我的工资自然更好

喝过酒吗: 喝过,被我奶奶灌的

暗恋过几个人: 说出来不就不算暗了嘛

会因为害羞而不敢跟人表白吗:很有可能,但不是害羞吧,是惰性

不敢吃的东西: 虫子,狗肉

最喜欢吃的是什么东西: 自己做的话 酱油拌饭 番茄鸡蛋 香草蛋糕 有条件的话,腾冲大救驾,路边小摊

最喜欢喝什么: 冰水 牛奶 青山绿水(完全为了卖相)

最喜欢的数字: 7

最喜欢的电影: Amelie

喜欢看的哪一种电影类型: 有会说话的灯罩, 偏黄绿的色调, 没有很多人知道

最喜欢的卡通人物和品牌:Bob Squarepants, H&M

最怀念的日子: 过去三年的暑假

最伤心的经验: 秋末冬初

最喜欢星期几: 星期五 可以偷懒,而且不用担心明天,全球人都这样想吧

最喜欢春夏秋冬哪个季节: 原来偏向夏天,现在开始觉得秋天很上镜

喜欢的花: 细长的,一片片的,很低调的星点野花

喜欢的运动: 走路-->变速跑 每天上学时都要体验

喜欢的冰淇淋种类: 里面不要有太多果仁,讨厌核桃,不要会染色,其他都行

最怕什么东西: 粘滑的软体动物

讨厌做的事: 可以不做的事

擅长的事: 骗人,装样

卧室地毯的颜色: 一小块,粉紫色,这颜色打出字来怎么那么恶?看上去还不错的

以后想做什么职业: 用显微镜看一些东西,做笔记,坐飞机参加跨国会议, 可以不理我讨厌的人

你们家住几楼:2楼

你觉得碟仙如何: 不知道,我不喜欢冒险

你觉得自己十年后会在哪里: 在家。。。。嘿嘿,在一个冬天稍微短一点的国家

寄这封邮件给你的上一个人是谁: 伪善

无聊的时候你大多会做些什么: 发呆,很紧张地笑

住的最远距离的一个朋友是谁: 住得太远,不就没联系了,就忘记了

世界上最恼人的事: 不被别人理睬

世界上最好的事: 打工的时候客人给小费用纸币

觉得同性恋如何呢: 不觉得如何呢

对于没有把握的事情态度如何: 闭着眼睛跳进去

如果有人误会你:小心翼翼地示好,次数有限

如果有人误会你,又不听你解释: 写信,次数有限

有想过要怎么对付你讨厌的人吗: 不理睬他们

通常几点上床睡觉: 12am

你猜谁会最先回这封信: 没人

最不可能回复: 每人

现在心里最想见的人是谁: 未曾谋面的网友

想要几岁结婚: 三十之前,二十五之前领养个小孩

今天心情好吗: 不错,就是有点冷

有想过自杀吗: 不想了

希望谁回信:每人 ,我想着的人

现在在几点:21:33

真是消耗好时间的好办法

每当无聊的时候就重写一遍

前天写的

野草烧不尽,春风吹又生

现在几点: 20:47

你的全名: Dan Peng

你现在正在听谁的歌:The Zephyrs , When the sky comes down it comes down on you head,老是有几根弦噔~噔~地荡开

你在哪里读书(工作): 中不溜不破不算太不干净的PL,mtl,qc,ca

最后吃的一样东西是什么: 晚饭。。。自然是米饭,特殊一点的东西有木耳和香菇。

现在天气如何: 光脚踩着木地板会被冻伤

戴隐形眼睛吗: 不戴,怎么不问我戴不戴眼镜阿,这不问我就没有义务交待,你看我这态度也就知道了

上一次吹蜡烛的数目: 1

你通常吹熄这些蜡烛的日期: 星期一,化学有试验课

你们家养过什么:自残的松鼠,不会爬墙的藤,我

星座: 狮子

兄弟姐妹和他们的年龄: 没有

你有纹身吗: 没有,我耳洞都不敢有,怕感染

你喜欢你目前的生活吗: 还可以,有更多的时间可以用来看书就好了,如果老板补发他欠我的工资自然更好

喝过酒吗: 喝过,被我奶奶灌的

暗恋过几个人: 说出来不就不算暗了嘛

会因为害羞而不敢跟人表白吗:很有可能,但不是害羞吧,是惰性

不敢吃的东西: 虫子,狗肉

最喜欢吃的是什么东西: 自己做的话 酱油拌饭 番茄鸡蛋 香草蛋糕 有条件的话,腾冲大救驾,路边小摊

最喜欢喝什么: 冰水 牛奶 青山绿水(完全为了卖相)

最喜欢的数字: 7

最喜欢的电影: Amelie

喜欢看的哪一种电影类型: 有会说话的灯罩, 偏黄绿的色调, 没有很多人知道

最喜欢的卡通人物和品牌:Bob Squarepants, H&M

最怀念的日子: 过去三年的暑假

最伤心的经验: 秋末冬初

最喜欢星期几: 星期五 可以偷懒,而且不用担心明天,全球人都这样想吧

最喜欢春夏秋冬哪个季节: 原来偏向夏天,现在开始觉得秋天很上镜

喜欢的花: 细长的,一片片的,很低调的星点野花

喜欢的运动: 走路-->变速跑 每天上学时都要体验

喜欢的冰淇淋种类: 里面不要有太多果仁,讨厌核桃,不要会染色,其他都行

最怕什么东西: 粘滑的软体动物

讨厌做的事: 可以不做的事

擅长的事: 骗人,装样

卧室地毯的颜色: 一小块,粉紫色,这颜色打出字来怎么那么恶?看上去还不错的

以后想做什么职业: 用显微镜看一些东西,做笔记,坐飞机参加跨国会议, 可以不理我讨厌的人

你们家住几楼:2楼

你觉得碟仙如何: 不知道,我不喜欢冒险

你觉得自己十年后会在哪里: 在家。。。。嘿嘿,在一个冬天稍微短一点的国家

寄这封邮件给你的上一个人是谁: 伪善

无聊的时候你大多会做些什么: 发呆,很紧张地笑

住的最远距离的一个朋友是谁: 住得太远,不就没联系了,就忘记了

世界上最恼人的事: 不被别人理睬

世界上最好的事: 打工的时候客人给小费用纸币

觉得同性恋如何呢: 不觉得如何呢

对于没有把握的事情态度如何: 闭着眼睛跳进去

如果有人误会你:小心翼翼地示好,次数有限

如果有人误会你,又不听你解释: 写信,次数有限

有想过要怎么对付你讨厌的人吗: 不理睬他们

通常几点上床睡觉: 12am

你猜谁会最先回这封信: 没人

最不可能回复: 每人

现在心里最想见的人是谁: 未曾谋面的网友

想要几岁结婚: 三十之前,二十五之前领养个小孩

今天心情好吗: 不错,就是有点冷

有想过自杀吗: 不想了

希望谁回信:每人 ,我想着的人

现在在几点:21:33

真是消耗好时间的好办法

每当无聊的时候就重写一遍

Wednesday, November 17, 2004

Tuesday, November 16, 2004

Sing a song of two pennies

从秋天完结的时候开始,

莫名其妙的难过。

就算是有很蓝的天空,很白的云朵,很灿烂的阳光,很凛冽的风,还是难过。

这已经超越了郁闷的境界了。

很多人问我,为什么难过?

我也想,是啊,为什么?

打开电视就可以看到濒危的珍稀动物,营养不良性水肿的非洲孩子,

两者都用又黑又亮的眼睛望着我。

面对他们,我怎么好意思说自己难过。

可是你如果让偷猎者在大街上对我紧追不舍,剥夺我的微薄财产,每天让我喝菜豆汤,或者什么都不吃,我说

不定就不难过了。

很多小事,小到单独分开都看不到,一起倾覆,拢起来,张开手都抱不住。

在学校里,坐在课桌旁,可以抱着头说,忙死了,忙死了,再缺时间就真的死人了。

在光秃秃的街上被风吹半个小时之后,我究竟在忙什么突然忘记了。

在家里,我继续坐在桌前,抱着头说,闲死了,闲死了,再没事干就真的死人了。

难道这两个世界真得不能被统一?

让我难过的事有:

一些我在乎的人不理我了

我不得不理睬一些我在乎的人

明天是Liette的生日,今天她给了暗示,我却完全忘记准备礼物了。

一些塔罗牌,翻译了两个月了,还是没头绪。

星期四就是Ste-Cecile,我只去了一次排练。

得在周末之前把摄像机和采访的事落实了。

下周四之前做好montage.

明天还得写所谓的惊愕短篇小说。

Concerto还没有背下来,不知道到时候老师的脸色。。。。

账号很久没有进的钱了。

Mp3和CD机都罢工了

手套不见了一只,另一只很孤单。

图书馆的书通通到期,没能续,要罚款。

有人说,难过的时候,深呼吸,学一条金鱼,腮帮扑通扑通。

我不要再难过。

莫名其妙的难过。

就算是有很蓝的天空,很白的云朵,很灿烂的阳光,很凛冽的风,还是难过。

这已经超越了郁闷的境界了。

很多人问我,为什么难过?

我也想,是啊,为什么?

打开电视就可以看到濒危的珍稀动物,营养不良性水肿的非洲孩子,

两者都用又黑又亮的眼睛望着我。

面对他们,我怎么好意思说自己难过。

可是你如果让偷猎者在大街上对我紧追不舍,剥夺我的微薄财产,每天让我喝菜豆汤,或者什么都不吃,我说

不定就不难过了。

很多小事,小到单独分开都看不到,一起倾覆,拢起来,张开手都抱不住。

在学校里,坐在课桌旁,可以抱着头说,忙死了,忙死了,再缺时间就真的死人了。

在光秃秃的街上被风吹半个小时之后,我究竟在忙什么突然忘记了。

在家里,我继续坐在桌前,抱着头说,闲死了,闲死了,再没事干就真的死人了。

难道这两个世界真得不能被统一?

让我难过的事有:

一些我在乎的人不理我了

我不得不理睬一些我在乎的人

明天是Liette的生日,今天她给了暗示,我却完全忘记准备礼物了。

一些塔罗牌,翻译了两个月了,还是没头绪。

星期四就是Ste-Cecile,我只去了一次排练。

得在周末之前把摄像机和采访的事落实了。

下周四之前做好montage.

明天还得写所谓的惊愕短篇小说。

Concerto还没有背下来,不知道到时候老师的脸色。。。。

账号很久没有进的钱了。

Mp3和CD机都罢工了

手套不见了一只,另一只很孤单。

图书馆的书通通到期,没能续,要罚款。

有人说,难过的时候,深呼吸,学一条金鱼,腮帮扑通扑通。

我不要再难过。

The country of depression

by: Evelyn Lau

essay from: OUT reflections on a life so far

typed~ hic

Please notify me if you find any typo

It began there, in that time between childhood and adulthood. How I loathed my life, my newly adolescent self! It was the usual resume of teenage misery, unremarkable in the end. Everything around me seemed thick and woolly and static -- the unwavering street outside the window of our little house, with a torturous glimpse of the down town lights in the distance, like a mirage I would never reach. The pudgy flesh I was gaining from my secret food binges made me feel leaden and sluggish. The texture of my skin, the oil in my hair, my ugly, scratchy clothes -- everything felt wrong, repulsive. I often prayed I would die in my sleep, so I would not have to face another day at school as an outcast. [...]

But when I next open my eyes there would be the familiar grey light through the window, and the depression would descend like a blanket. If it was winter it would be dark, and I would go to the kitchen to eat breakfast next to my father before he headed out on yet another of his unsuccessful job searches. The linoleum cold beneath our feet, our silent, awkward chewing. I would look at the soft slices of bread on my plate, how they broke apart under the jab of my knife with its dab of butter no matter how carefully I tried to spread it, and rage would course through my body. Why couldn't I butter a piece of bread without it falling apart? Why couldn't I be perfect? I wanted to take the entire loaf of bread in my hands, smear it with butter and honey, smash it in my hands, and hurl it against the wall. Perhaps then my father would rise from the icy lake of his torment, his unhappy eyes would focus, and he would see me.

I thought of suicide constantly; what likely stopped me was the thought of the trouble I would get into from my parents if I tried and didn't succeed. In the meantime, every day was a small eternity to be endured. The light in my memory of this time seems always to be charcoal grey, or black. The air felt thick in my nostrils and throat, and the depression expanded to fill the days, weeks, and months with its massive, rolling fog.

I was twelve, or thirteen. Younger, even. Perhaps it went on for months, stopped for a while, then started again; perhaps it continued for years, with only days of remission in between. Why can't I remember? Time meant something different then, and what seemed like years might only have been months, or weeks. But I remember looking at a calendar on my bedroom wall on which I had crossed out the days with big ink Xs, flipping back through the months and realizing I had been depressed for most of the tear. The memory of this is murky, a swamp of mornings waking in darkness, fear throbbing in a tight knot in my chest, and then the long day ahead wrapped in grey cotton. This state was different from pain, or panic, which I had known earlier -- those emotions arrived, were experienced, then left like their brighter counterparts. You survived them, and they had an acuity that depression, in its muffling weight, lacked. When I was depressed I would have given anything for a sharp, precise emotion, even if it was only sadness. Depression had no edges and therefore no borders, no discernible beginning or end.

Doctors claim that serious depressions are often triggered by loss, or by an accumulation of losses. Perhaps I was mourning the loss of the time when we had been more or less happy, as families go, before my father became unemployed and retreated to the dark basement in shame, before my mother became increasingly hysterical and stalked through the house terrifying me with her unpredictable moods and preoccupations. Before the arrival of my sister, who sat curled up in the crook of my father's arm while I watched from a sullen distance, murdering her in my mind. Perhaps I anticipated the unrecoverable loss that lay ahead, the day when as a fourteen-year-old I would walk out the door of my parents' house and never look back.

And then it went away. Or, perhaps, the depression remained but there but there was little room for it. I left home and tumbled into one crisis after another -- drugs, prostitution, suicide attempts, sleeping on the streets. Depression was elbowed aside by the immediacy of fear, by the cartoon nausea of bad LSD trips and drug overdoses, by struggling daily to survive. In retrospect, perhaps all that behavior was a form of self-medication. It was still better than the cotton-packed days of depression, which I learned to quickly eradicate with a handful of pills, a cupful of methadone, several tricks turned in a row.

In my early to mid-twenties the fog thinned and then seemed to lift for good. When I woke, the clear day lay ahead. I could intellectually recall the fact that I had been depressed -- I restricted it to a period in my early adolescence -- but could no longer feel it viscerally. It was like recalling a migraine, a pinched nerve, the time when you were at the kitchen counter and the knife slipped and sliced your finger open. You could describe it in some detail afterwards, but the memory of the pain would be less than a shadow of itself. This is how the body heals, how the mind closes over pain like scar tissue over a wound. When people I knew complained about being depressed, I had to swallow my impatience with them. I thought that at least they should have the grace to keep it to themselves, since there was nothing so dispiriting as listening to people almost lovingly explain the topology of their depression. The relentlessness of it, the iron lid over all their days. At least if they were experiencing a particular crisis there was heightened feeling, and you could offer a shoulder to cry on, a suggestion for action that they had overlooked, even a solution to their problems. Depression was something that simply went on and on, and wore out everyone around the depressed person.

I would try to sympathize by saying that I, too, had gone through a period of depression in my early teens. But that was all it was in my memory: a bleak, sluggish period, a long time ago. I never ceased to be grateful for its departure, though. I did remember that it had seemed worse than the most piercing pain, and so even when there was turmoil in my life, and grief, I was glad that it didn't devolve into depression. I began to think of that bleak band of time before running away as unique to a teenager's changing hormones and my circumstances at home; I saw myself as safely beyond its reach.

Then something happened. The doctors say that one serious depression puts you at risk for another during the course of your lifetime; two increases the likelihood of a third, and so on. You may not even be aware of the gravity of the precipitating losses at the time; you may think you are dealing with them just fine, that indeed you've dealt with a lot worse in the past. But then one morning you wake and discover that the fog has crept in overnight. It is banked out in the streets, so heavily that the outlines of the buildings in your familiar city are lost. There are no streets or mountains, no glimmer of water. It is in the room with you, pressing down over your nose and throat and almost suffocating you. You try to rise, to live your normal day, and discover that you can't get out of bed. You are as immobilized as if you had had a stroke in the middle of the night, while you slept. But this is ridiculous, you think. Nothing's wrong with me. All I have to do is get up, the way I've done every other day, without thinking about it. And yet you can't.

What happened to cause this depression? It took about a year to develop. Each loss, by itself, was not a cause for collapse. When I count them they fit on the fingers of one hand; they seem embarrassing in their slightness. Some setbacks and problems at work, several troubled relationships that ended badly. But these events occurred within a year and somehow, taken together, the impact they had was greater than the sum of their individual parts. I slid into depression, imperceptibly at first, then rapidly. I could not write for months on end, plagued instead by obsessive thoughts and memories. The depression that had been lurking -- sneaking in under the closed door, around the window frames, filling my room slowly with smoke -- poured in and sealed me shut inside its grey heart.

An acquaintance once described to me what it was like when her back went out and she couldn't get out of bed without considerable pain. She would lie on her mattress visualizing herself to the bathroom, then down the carpeted stairs to the kitchen. As she did this in her mind, she counted the steps necessary to reach each destination; these small journeys she had once made without thought had suddenly become momentous.

I found myself wishing I had some physical explanation for the mornings when I lay in bed unable to make those same journeys. The depression, often accompanied by a racing heartbeat, was there in the room as soon as I woke. It was in that first silver of consciousness in that instant before I was aware of the light through the blinds, or of who I was. Some mornings, miraculously, it wasn't there, and I got out of bed and started the day like a normal person. But most mornings its iron bars locked down my limbs. It had a weight to it, like a mattress. I lay unmoving, and even if there were stripes of baby-blue sky and sunlight through the blinds, my mind was bathed in grey. I was flooded with the same nameless, nauseating terror that a friend who once complained about his depression had described -- an unfocused sense of impending doom, as of your own death or dismemberment, made more unbearable because it was without cause. You could not say, Well, I'm lying here frightened to death because I have just lost my life's savings, or I have been diagnosed with cancer, or there is a stranger in the room standing over me holding an axe. There is only your hammering heartbeat and the black curtain dropping down across your mind.

[...]

Before the depression -- and it was like that, there was a time before and then a time after -- I loved dinner parties. The conversations, the food and wine, the warm company of friends, the stimulating addition of strangers. After the depression came, dinner parties were to be endured, and I didn't always know how. I would arrive early, hoping that would compensate for the fact that I would inevitably be the first to leave. At first I drank too much, hoping to recover some sparkle or sheen, the verbal faculty and the capacity for enjoying the company of others that I had lost. For a while, alcohol presented itself as a viable cure for depression -- it poured a bright glaze over my vision, improved my affect, restored some cheer. I would feel a rush of energy and bonhomie, my tongue would loosen and words would trip out as easily as they once used to. But, of course, the depression the next day would be that much worse, and eventually I began to limit myself to two or three drinks over the course of long dinners. Thus I would be sober -- in every sense of the word. Moribund, really. In a way, this was worse. Around the table people would be rocking with laughter, gesticulating, their voices rising in volume, conversations competing with each other in noise and conviction. I strained to laugh along, weakly, in order to convince the host that I was having a good time even though I wasn't adding to the conversation. I stared at the faces around me, their mouths gasping, their eyes shiny and intoxicated, their laughter louder than jackhammers. I looked blankly at the rows of exposed teeth and gum, and it seemed I could see, with a sort of detached X-ray vision, the skulls beneath the stretched skin. That was all these people were, skeletons temporarily covered with flesh and pretense. I wanted to cover my ears with my hands. Somewhere in the multiple threads of conversation there was a story, a joke, but I could not follow it, could not catch it. Their voices assailed me from all sides in a cacophony. I let myself drift, dreaming of my white bed, my soft square of sleep. In the bathroom, away from the loud guests. I would look at myself in the mirror, where my face appeared round and puffy from too much sleep, waiting a few merciful, quiet minutes before ducking back out to the party as into a hail of bullets.

Often, someone would say something that would send me into a rage. It is said that depression is rage turned inwards, rage given no other outlet. I thought of depression as the grey side of a coin that is scarlet on its reverse. The rage was always lurking; a woman's hooting laughter in a darkened theatre would not simply irritate, it would touch off in me the entire store of built-up rage, completely unrelated to her. I would hunch in my seat, weaving an elaborate fantasy of torturing, raping, and murdering her. Someone would say something seemingly innocuous, and my blood would choke as it boiled. I would feel as if I were drowning in a sea of red; I would try to stay on the surface, but wave after would submerge me. I had not known anger like this since my adolescence, my childhood -- the sort of rage that comes when you are accused of something you haven't done, or when a repulsive stranger is running his hands over your body. It was a child's anger, uncontainable, overwhelming. It was all I knew. I swallowed and tried to hold it back, but my heart would be racing and it would take everything not to crush the wineglass in my hand, to feel shards of glass bristling out of my flesh, or throw it against the wall and watch the pieces rain down. I practically panted with the effort of holding back, and though I never did what I wanted to do -- mostly because I would suddenly have a clear and terrifying memory of my schizophrenic aunt, who when I was a child would throw dishes against the wall during dinner in an attack of rage and paranoia -- I did derail a few social occasions with the anger I couldn't stop from spilling over. It shamed me, this impotent rage, this impatience with the people around me -- their little habits, which I had previously barely noticed, now irritated me so much I wanted to claw their faces until they bled. How do you admit such monstrous thoughts, even to yourself? But that was the severity of it. Something that might once have been a minor irritation, a fly buzzing in another room of the house, was now nails running down a chalkboard next to my ear.

[...]

How different is one person's tale of depression from another's? Is it often only the same story? Writing this essay, I was afraid to read the work of other people who had written in detail about their depressions -- I worried that not would the story be the same, but we would have somehow found the same language to describe it. The same phrases, the same words. How many ways are there to examine this litany of inertia, anxiety, anger and detachment? To describe a mental landscape from which all pleasure has drained, leaving it like, I imagine, the surface of the moon, pitted and barren? How could an affliction that feels so personal and singular, and in many ways inexpressible, actually be shared by so many? Like those ads that appear from time to time in the newspaper, run by some university or research group: "Are you depressed?" and, following, some of the symptoms. You recognize yourself, but it seems as generic as those pamphlets in the doctor’s office asking if you are an alcoholic, and you are because you, too, have lied about your drinking, missed work because of it, drink because you are nervous in social situations, etc.

[...]

Depression often seems to be accompanied by a certain level of narcissism. Its sufferers are always telling you how they feel, always checking the barometer of their emotional weather. They issue reports on it as they would on a matter of national significance. When I talk to my depressed acquaintances, their unhappiness becomes a claim on my attention and concern. A simple “How are you?" will elicit a detailed report on the person's recent moods and emotional states. This is the world they have come to occupy, the one they are trapped inside, and for all they know it has taken on the dimensions of the physical world itself. There is no other news, no weather or wars in another hemisphere. When you are not depressed yourself, it is a difficult state to tolerate in another. There is no visible wound to bandage, no doctor's pronouncement of a terminal illness with which to sympathize. There is only the unspooling of the grey ribbon of their days. You want to order them to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, to take a good look around those around them who are less fortunate and yet still manage to notice the sun shining in the sky, the first tulips pushing out of the earth. [...]

Their voices on the phone, disembodied, are instant indicators of their emotional states. When they are depressed, the usual highs and lows of infliction, of life and curiosity and enthusiasm, are drained away. Sometimes they cry, and then they sound like children, inconsolable.

[...]

I have never taken an antidepressant, and thus cannot describe -- though the writer in me would like to -- the physical and emotional changes, the sway and lift, the swirling sparkling grainy patterns of behavior breaking apart and re-forming. I wonder what about me would change, and cannot imagine the world emerging from under the shadow of certain depressive behaviors -- the sun coming out and a crisp slant to the architecture, everything clearly delineated, unmuddied. What would it be like to be free of those burdens, how many more hours in the day would there suddenly be to learn something new? Would my thoughts stop rotating obsessively around the tracks and grooves worn into my mind? Would I suddenly be free of whatever it is that immobilizes me, tethers me firmly to the past? It is a short leash that extends only so far as I strain towards defining a new life for myself, my own life, away prom parental expectations and childhood experiences that redefine, over and over, all my relationships -- from the most casual conversation with the grocery clerk to the most intimate sexual entanglement -- so that it sometimes seems to me that our fate is to live out our lives replaying what hurt us, what was taken away from us or denied us when we were small, watchful, easily damaged creatures.

What has stopped me from trying antidepressants, at least as an experiment, is the fear, of course, that

It began there, in that time between childhood and adulthood. How I loathed my life, my newly adolescent self! It was the usual resume of teenage misery, unremarkable in the end. Everything around me seemed thick and woolly and static -- the unwavering street outside the window of our little house, with a torturous glimpse of the down town lights in the distance, like a mirage I would never reach. The pudgy flesh I was gaining from my secret food binges made me feel leaden and sluggish. The texture of my skin, the oil in my hair, my ugly, scratchy clothes -- everything felt wrong, repulsive. I often prayed I would die in my sleep, so I would not have to face another day at school as an outcast. [...]

But when I next open my eyes there would be the familiar grey light through the window, and the depression would descend like a blanket. If it was winter it would be dark, and I would go to the kitchen to eat breakfast next to my father before he headed out on yet another of his unsuccessful job searches. The linoleum cold beneath our feet, our silent, awkward chewing. I would look at the soft slices of bread on my plate, how they broke apart under the jab of my knife with its dab of butter no matter how carefully I tried to spread it, and rage would course through my body. Why couldn't I butter a piece of bread without it falling apart? Why couldn't I be perfect? I wanted to take the entire loaf of bread in my hands, smear it with butter and honey, smash it in my hands, and hurl it against the wall. Perhaps then my father would rise from the icy lake of his torment, his unhappy eyes would focus, and he would see me.

I thought of suicide constantly; what likely stopped me was the thought of the trouble I would get into from my parents if I tried and didn't succeed. In the meantime, every day was a small eternity to be endured. The light in my memory of this time seems always to be charcoal grey, or black. The air felt thick in my nostrils and throat, and the depression expanded to fill the days, weeks, and months with its massive, rolling fog.

I was twelve, or thirteen. Younger, even. Perhaps it went on for months, stopped for a while, then started again; perhaps it continued for years, with only days of remission in between. Why can't I remember? Time meant something different then, and what seemed like years might only have been months, or weeks. But I remember looking at a calendar on my bedroom wall on which I had crossed out the days with big ink Xs, flipping back through the months and realizing I had been depressed for most of the tear. The memory of this is murky, a swamp of mornings waking in darkness, fear throbbing in a tight knot in my chest, and then the long day ahead wrapped in grey cotton. This state was different from pain, or panic, which I had known earlier -- those emotions arrived, were experienced, then left like their brighter counterparts. You survived them, and they had an acuity that depression, in its muffling weight, lacked. When I was depressed I would have given anything for a sharp, precise emotion, even if it was only sadness. Depression had no edges and therefore no borders, no discernible beginning or end.

Doctors claim that serious depressions are often triggered by loss, or by an accumulation of losses. Perhaps I was mourning the loss of the time when we had been more or less happy, as families go, before my father became unemployed and retreated to the dark basement in shame, before my mother became increasingly hysterical and stalked through the house terrifying me with her unpredictable moods and preoccupations. Before the arrival of my sister, who sat curled up in the crook of my father's arm while I watched from a sullen distance, murdering her in my mind. Perhaps I anticipated the unrecoverable loss that lay ahead, the day when as a fourteen-year-old I would walk out the door of my parents' house and never look back.

And then it went away. Or, perhaps, the depression remained but there but there was little room for it. I left home and tumbled into one crisis after another -- drugs, prostitution, suicide attempts, sleeping on the streets. Depression was elbowed aside by the immediacy of fear, by the cartoon nausea of bad LSD trips and drug overdoses, by struggling daily to survive. In retrospect, perhaps all that behavior was a form of self-medication. It was still better than the cotton-packed days of depression, which I learned to quickly eradicate with a handful of pills, a cupful of methadone, several tricks turned in a row.

In my early to mid-twenties the fog thinned and then seemed to lift for good. When I woke, the clear day lay ahead. I could intellectually recall the fact that I had been depressed -- I restricted it to a period in my early adolescence -- but could no longer feel it viscerally. It was like recalling a migraine, a pinched nerve, the time when you were at the kitchen counter and the knife slipped and sliced your finger open. You could describe it in some detail afterwards, but the memory of the pain would be less than a shadow of itself. This is how the body heals, how the mind closes over pain like scar tissue over a wound. When people I knew complained about being depressed, I had to swallow my impatience with them. I thought that at least they should have the grace to keep it to themselves, since there was nothing so dispiriting as listening to people almost lovingly explain the topology of their depression. The relentlessness of it, the iron lid over all their days. At least if they were experiencing a particular crisis there was heightened feeling, and you could offer a shoulder to cry on, a suggestion for action that they had overlooked, even a solution to their problems. Depression was something that simply went on and on, and wore out everyone around the depressed person.

I would try to sympathize by saying that I, too, had gone through a period of depression in my early teens. But that was all it was in my memory: a bleak, sluggish period, a long time ago. I never ceased to be grateful for its departure, though. I did remember that it had seemed worse than the most piercing pain, and so even when there was turmoil in my life, and grief, I was glad that it didn't devolve into depression. I began to think of that bleak band of time before running away as unique to a teenager's changing hormones and my circumstances at home; I saw myself as safely beyond its reach.

Then something happened. The doctors say that one serious depression puts you at risk for another during the course of your lifetime; two increases the likelihood of a third, and so on. You may not even be aware of the gravity of the precipitating losses at the time; you may think you are dealing with them just fine, that indeed you've dealt with a lot worse in the past. But then one morning you wake and discover that the fog has crept in overnight. It is banked out in the streets, so heavily that the outlines of the buildings in your familiar city are lost. There are no streets or mountains, no glimmer of water. It is in the room with you, pressing down over your nose and throat and almost suffocating you. You try to rise, to live your normal day, and discover that you can't get out of bed. You are as immobilized as if you had had a stroke in the middle of the night, while you slept. But this is ridiculous, you think. Nothing's wrong with me. All I have to do is get up, the way I've done every other day, without thinking about it. And yet you can't.

What happened to cause this depression? It took about a year to develop. Each loss, by itself, was not a cause for collapse. When I count them they fit on the fingers of one hand; they seem embarrassing in their slightness. Some setbacks and problems at work, several troubled relationships that ended badly. But these events occurred within a year and somehow, taken together, the impact they had was greater than the sum of their individual parts. I slid into depression, imperceptibly at first, then rapidly. I could not write for months on end, plagued instead by obsessive thoughts and memories. The depression that had been lurking -- sneaking in under the closed door, around the window frames, filling my room slowly with smoke -- poured in and sealed me shut inside its grey heart.

An acquaintance once described to me what it was like when her back went out and she couldn't get out of bed without considerable pain. She would lie on her mattress visualizing herself to the bathroom, then down the carpeted stairs to the kitchen. As she did this in her mind, she counted the steps necessary to reach each destination; these small journeys she had once made without thought had suddenly become momentous.

I found myself wishing I had some physical explanation for the mornings when I lay in bed unable to make those same journeys. The depression, often accompanied by a racing heartbeat, was there in the room as soon as I woke. It was in that first silver of consciousness in that instant before I was aware of the light through the blinds, or of who I was. Some mornings, miraculously, it wasn't there, and I got out of bed and started the day like a normal person. But most mornings its iron bars locked down my limbs. It had a weight to it, like a mattress. I lay unmoving, and even if there were stripes of baby-blue sky and sunlight through the blinds, my mind was bathed in grey. I was flooded with the same nameless, nauseating terror that a friend who once complained about his depression had described -- an unfocused sense of impending doom, as of your own death or dismemberment, made more unbearable because it was without cause. You could not say, Well, I'm lying here frightened to death because I have just lost my life's savings, or I have been diagnosed with cancer, or there is a stranger in the room standing over me holding an axe. There is only your hammering heartbeat and the black curtain dropping down across your mind.

[...]

Before the depression -- and it was like that, there was a time before and then a time after -- I loved dinner parties. The conversations, the food and wine, the warm company of friends, the stimulating addition of strangers. After the depression came, dinner parties were to be endured, and I didn't always know how. I would arrive early, hoping that would compensate for the fact that I would inevitably be the first to leave. At first I drank too much, hoping to recover some sparkle or sheen, the verbal faculty and the capacity for enjoying the company of others that I had lost. For a while, alcohol presented itself as a viable cure for depression -- it poured a bright glaze over my vision, improved my affect, restored some cheer. I would feel a rush of energy and bonhomie, my tongue would loosen and words would trip out as easily as they once used to. But, of course, the depression the next day would be that much worse, and eventually I began to limit myself to two or three drinks over the course of long dinners. Thus I would be sober -- in every sense of the word. Moribund, really. In a way, this was worse. Around the table people would be rocking with laughter, gesticulating, their voices rising in volume, conversations competing with each other in noise and conviction. I strained to laugh along, weakly, in order to convince the host that I was having a good time even though I wasn't adding to the conversation. I stared at the faces around me, their mouths gasping, their eyes shiny and intoxicated, their laughter louder than jackhammers. I looked blankly at the rows of exposed teeth and gum, and it seemed I could see, with a sort of detached X-ray vision, the skulls beneath the stretched skin. That was all these people were, skeletons temporarily covered with flesh and pretense. I wanted to cover my ears with my hands. Somewhere in the multiple threads of conversation there was a story, a joke, but I could not follow it, could not catch it. Their voices assailed me from all sides in a cacophony. I let myself drift, dreaming of my white bed, my soft square of sleep. In the bathroom, away from the loud guests. I would look at myself in the mirror, where my face appeared round and puffy from too much sleep, waiting a few merciful, quiet minutes before ducking back out to the party as into a hail of bullets.

Often, someone would say something that would send me into a rage. It is said that depression is rage turned inwards, rage given no other outlet. I thought of depression as the grey side of a coin that is scarlet on its reverse. The rage was always lurking; a woman's hooting laughter in a darkened theatre would not simply irritate, it would touch off in me the entire store of built-up rage, completely unrelated to her. I would hunch in my seat, weaving an elaborate fantasy of torturing, raping, and murdering her. Someone would say something seemingly innocuous, and my blood would choke as it boiled. I would feel as if I were drowning in a sea of red; I would try to stay on the surface, but wave after would submerge me. I had not known anger like this since my adolescence, my childhood -- the sort of rage that comes when you are accused of something you haven't done, or when a repulsive stranger is running his hands over your body. It was a child's anger, uncontainable, overwhelming. It was all I knew. I swallowed and tried to hold it back, but my heart would be racing and it would take everything not to crush the wineglass in my hand, to feel shards of glass bristling out of my flesh, or throw it against the wall and watch the pieces rain down. I practically panted with the effort of holding back, and though I never did what I wanted to do -- mostly because I would suddenly have a clear and terrifying memory of my schizophrenic aunt, who when I was a child would throw dishes against the wall during dinner in an attack of rage and paranoia -- I did derail a few social occasions with the anger I couldn't stop from spilling over. It shamed me, this impotent rage, this impatience with the people around me -- their little habits, which I had previously barely noticed, now irritated me so much I wanted to claw their faces until they bled. How do you admit such monstrous thoughts, even to yourself? But that was the severity of it. Something that might once have been a minor irritation, a fly buzzing in another room of the house, was now nails running down a chalkboard next to my ear.

[...]

How different is one person's tale of depression from another's? Is it often only the same story? Writing this essay, I was afraid to read the work of other people who had written in detail about their depressions -- I worried that not would the story be the same, but we would have somehow found the same language to describe it. The same phrases, the same words. How many ways are there to examine this litany of inertia, anxiety, anger and detachment? To describe a mental landscape from which all pleasure has drained, leaving it like, I imagine, the surface of the moon, pitted and barren? How could an affliction that feels so personal and singular, and in many ways inexpressible, actually be shared by so many? Like those ads that appear from time to time in the newspaper, run by some university or research group: "Are you depressed?" and, following, some of the symptoms. You recognize yourself, but it seems as generic as those pamphlets in the doctor’s office asking if you are an alcoholic, and you are because you, too, have lied about your drinking, missed work because of it, drink because you are nervous in social situations, etc.

[...]

Depression often seems to be accompanied by a certain level of narcissism. Its sufferers are always telling you how they feel, always checking the barometer of their emotional weather. They issue reports on it as they would on a matter of national significance. When I talk to my depressed acquaintances, their unhappiness becomes a claim on my attention and concern. A simple “How are you?" will elicit a detailed report on the person's recent moods and emotional states. This is the world they have come to occupy, the one they are trapped inside, and for all they know it has taken on the dimensions of the physical world itself. There is no other news, no weather or wars in another hemisphere. When you are not depressed yourself, it is a difficult state to tolerate in another. There is no visible wound to bandage, no doctor's pronouncement of a terminal illness with which to sympathize. There is only the unspooling of the grey ribbon of their days. You want to order them to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, to take a good look around those around them who are less fortunate and yet still manage to notice the sun shining in the sky, the first tulips pushing out of the earth. [...]

Their voices on the phone, disembodied, are instant indicators of their emotional states. When they are depressed, the usual highs and lows of infliction, of life and curiosity and enthusiasm, are drained away. Sometimes they cry, and then they sound like children, inconsolable.

[...]

I have never taken an antidepressant, and thus cannot describe -- though the writer in me would like to -- the physical and emotional changes, the sway and lift, the swirling sparkling grainy patterns of behavior breaking apart and re-forming. I wonder what about me would change, and cannot imagine the world emerging from under the shadow of certain depressive behaviors -- the sun coming out and a crisp slant to the architecture, everything clearly delineated, unmuddied. What would it be like to be free of those burdens, how many more hours in the day would there suddenly be to learn something new? Would my thoughts stop rotating obsessively around the tracks and grooves worn into my mind? Would I suddenly be free of whatever it is that immobilizes me, tethers me firmly to the past? It is a short leash that extends only so far as I strain towards defining a new life for myself, my own life, away prom parental expectations and childhood experiences that redefine, over and over, all my relationships -- from the most casual conversation with the grocery clerk to the most intimate sexual entanglement -- so that it sometimes seems to me that our fate is to live out our lives replaying what hurt us, what was taken away from us or denied us when we were small, watchful, easily damaged creatures.

To Be Entered...

Background Information.

Born in 1971, Evelyn Lau is the daughter of a chinese immigrant family.....

She works and lives in Vancouver.

essay from: OUT reflections on a life so far

typed~ hic

Please notify me if you find any typo

It began there, in that time between childhood and adulthood. How I loathed my life, my newly adolescent self! It was the usual resume of teenage misery, unremarkable in the end. Everything around me seemed thick and woolly and static -- the unwavering street outside the window of our little house, with a torturous glimpse of the down town lights in the distance, like a mirage I would never reach. The pudgy flesh I was gaining from my secret food binges made me feel leaden and sluggish. The texture of my skin, the oil in my hair, my ugly, scratchy clothes -- everything felt wrong, repulsive. I often prayed I would die in my sleep, so I would not have to face another day at school as an outcast. [...]

But when I next open my eyes there would be the familiar grey light through the window, and the depression would descend like a blanket. If it was winter it would be dark, and I would go to the kitchen to eat breakfast next to my father before he headed out on yet another of his unsuccessful job searches. The linoleum cold beneath our feet, our silent, awkward chewing. I would look at the soft slices of bread on my plate, how they broke apart under the jab of my knife with its dab of butter no matter how carefully I tried to spread it, and rage would course through my body. Why couldn't I butter a piece of bread without it falling apart? Why couldn't I be perfect? I wanted to take the entire loaf of bread in my hands, smear it with butter and honey, smash it in my hands, and hurl it against the wall. Perhaps then my father would rise from the icy lake of his torment, his unhappy eyes would focus, and he would see me.

I thought of suicide constantly; what likely stopped me was the thought of the trouble I would get into from my parents if I tried and didn't succeed. In the meantime, every day was a small eternity to be endured. The light in my memory of this time seems always to be charcoal grey, or black. The air felt thick in my nostrils and throat, and the depression expanded to fill the days, weeks, and months with its massive, rolling fog.

I was twelve, or thirteen. Younger, even. Perhaps it went on for months, stopped for a while, then started again; perhaps it continued for years, with only days of remission in between. Why can't I remember? Time meant something different then, and what seemed like years might only have been months, or weeks. But I remember looking at a calendar on my bedroom wall on which I had crossed out the days with big ink Xs, flipping back through the months and realizing I had been depressed for most of the tear. The memory of this is murky, a swamp of mornings waking in darkness, fear throbbing in a tight knot in my chest, and then the long day ahead wrapped in grey cotton. This state was different from pain, or panic, which I had known earlier -- those emotions arrived, were experienced, then left like their brighter counterparts. You survived them, and they had an acuity that depression, in its muffling weight, lacked. When I was depressed I would have given anything for a sharp, precise emotion, even if it was only sadness. Depression had no edges and therefore no borders, no discernible beginning or end.

Doctors claim that serious depressions are often triggered by loss, or by an accumulation of losses. Perhaps I was mourning the loss of the time when we had been more or less happy, as families go, before my father became unemployed and retreated to the dark basement in shame, before my mother became increasingly hysterical and stalked through the house terrifying me with her unpredictable moods and preoccupations. Before the arrival of my sister, who sat curled up in the crook of my father's arm while I watched from a sullen distance, murdering her in my mind. Perhaps I anticipated the unrecoverable loss that lay ahead, the day when as a fourteen-year-old I would walk out the door of my parents' house and never look back.

And then it went away. Or, perhaps, the depression remained but there but there was little room for it. I left home and tumbled into one crisis after another -- drugs, prostitution, suicide attempts, sleeping on the streets. Depression was elbowed aside by the immediacy of fear, by the cartoon nausea of bad LSD trips and drug overdoses, by struggling daily to survive. In retrospect, perhaps all that behavior was a form of self-medication. It was still better than the cotton-packed days of depression, which I learned to quickly eradicate with a handful of pills, a cupful of methadone, several tricks turned in a row.

In my early to mid-twenties the fog thinned and then seemed to lift for good. When I woke, the clear day lay ahead. I could intellectually recall the fact that I had been depressed -- I restricted it to a period in my early adolescence -- but could no longer feel it viscerally. It was like recalling a migraine, a pinched nerve, the time when you were at the kitchen counter and the knife slipped and sliced your finger open. You could describe it in some detail afterwards, but the memory of the pain would be less than a shadow of itself. This is how the body heals, how the mind closes over pain like scar tissue over a wound. When people I knew complained about being depressed, I had to swallow my impatience with them. I thought that at least they should have the grace to keep it to themselves, since there was nothing so dispiriting as listening to people almost lovingly explain the topology of their depression. The relentlessness of it, the iron lid over all their days. At least if they were experiencing a particular crisis there was heightened feeling, and you could offer a shoulder to cry on, a suggestion for action that they had overlooked, even a solution to their problems. Depression was something that simply went on and on, and wore out everyone around the depressed person.

I would try to sympathize by saying that I, too, had gone through a period of depression in my early teens. But that was all it was in my memory: a bleak, sluggish period, a long time ago. I never ceased to be grateful for its departure, though. I did remember that it had seemed worse than the most piercing pain, and so even when there was turmoil in my life, and grief, I was glad that it didn't devolve into depression. I began to think of that bleak band of time before running away as unique to a teenager's changing hormones and my circumstances at home; I saw myself as safely beyond its reach.

Then something happened. The doctors say that one serious depression puts you at risk for another during the course of your lifetime; two increases the likelihood of a third, and so on. You may not even be aware of the gravity of the precipitating losses at the time; you may think you are dealing with them just fine, that indeed you've dealt with a lot worse in the past. But then one morning you wake and discover that the fog has crept in overnight. It is banked out in the streets, so heavily that the outlines of the buildings in your familiar city are lost. There are no streets or mountains, no glimmer of water. It is in the room with you, pressing down over your nose and throat and almost suffocating you. You try to rise, to live your normal day, and discover that you can't get out of bed. You are as immobilized as if you had had a stroke in the middle of the night, while you slept. But this is ridiculous, you think. Nothing's wrong with me. All I have to do is get up, the way I've done every other day, without thinking about it. And yet you can't.

What happened to cause this depression? It took about a year to develop. Each loss, by itself, was not a cause for collapse. When I count them they fit on the fingers of one hand; they seem embarrassing in their slightness. Some setbacks and problems at work, several troubled relationships that ended badly. But these events occurred within a year and somehow, taken together, the impact they had was greater than the sum of their individual parts. I slid into depression, imperceptibly at first, then rapidly. I could not write for months on end, plagued instead by obsessive thoughts and memories. The depression that had been lurking -- sneaking in under the closed door, around the window frames, filling my room slowly with smoke -- poured in and sealed me shut inside its grey heart.

An acquaintance once described to me what it was like when her back went out and she couldn't get out of bed without considerable pain. She would lie on her mattress visualizing herself to the bathroom, then down the carpeted stairs to the kitchen. As she did this in her mind, she counted the steps necessary to reach each destination; these small journeys she had once made without thought had suddenly become momentous.

I found myself wishing I had some physical explanation for the mornings when I lay in bed unable to make those same journeys. The depression, often accompanied by a racing heartbeat, was there in the room as soon as I woke. It was in that first silver of consciousness in that instant before I was aware of the light through the blinds, or of who I was. Some mornings, miraculously, it wasn't there, and I got out of bed and started the day like a normal person. But most mornings its iron bars locked down my limbs. It had a weight to it, like a mattress. I lay unmoving, and even if there were stripes of baby-blue sky and sunlight through the blinds, my mind was bathed in grey. I was flooded with the same nameless, nauseating terror that a friend who once complained about his depression had described -- an unfocused sense of impending doom, as of your own death or dismemberment, made more unbearable because it was without cause. You could not say, Well, I'm lying here frightened to death because I have just lost my life's savings, or I have been diagnosed with cancer, or there is a stranger in the room standing over me holding an axe. There is only your hammering heartbeat and the black curtain dropping down across your mind.

[...]

Before the depression -- and it was like that, there was a time before and then a time after -- I loved dinner parties. The conversations, the food and wine, the warm company of friends, the stimulating addition of strangers. After the depression came, dinner parties were to be endured, and I didn't always know how. I would arrive early, hoping that would compensate for the fact that I would inevitably be the first to leave. At first I drank too much, hoping to recover some sparkle or sheen, the verbal faculty and the capacity for enjoying the company of others that I had lost. For a while, alcohol presented itself as a viable cure for depression -- it poured a bright glaze over my vision, improved my affect, restored some cheer. I would feel a rush of energy and bonhomie, my tongue would loosen and words would trip out as easily as they once used to. But, of course, the depression the next day would be that much worse, and eventually I began to limit myself to two or three drinks over the course of long dinners. Thus I would be sober -- in every sense of the word. Moribund, really. In a way, this was worse. Around the table people would be rocking with laughter, gesticulating, their voices rising in volume, conversations competing with each other in noise and conviction. I strained to laugh along, weakly, in order to convince the host that I was having a good time even though I wasn't adding to the conversation. I stared at the faces around me, their mouths gasping, their eyes shiny and intoxicated, their laughter louder than jackhammers. I looked blankly at the rows of exposed teeth and gum, and it seemed I could see, with a sort of detached X-ray vision, the skulls beneath the stretched skin. That was all these people were, skeletons temporarily covered with flesh and pretense. I wanted to cover my ears with my hands. Somewhere in the multiple threads of conversation there was a story, a joke, but I could not follow it, could not catch it. Their voices assailed me from all sides in a cacophony. I let myself drift, dreaming of my white bed, my soft square of sleep. In the bathroom, away from the loud guests. I would look at myself in the mirror, where my face appeared round and puffy from too much sleep, waiting a few merciful, quiet minutes before ducking back out to the party as into a hail of bullets.

Often, someone would say something that would send me into a rage. It is said that depression is rage turned inwards, rage given no other outlet. I thought of depression as the grey side of a coin that is scarlet on its reverse. The rage was always lurking; a woman's hooting laughter in a darkened theatre would not simply irritate, it would touch off in me the entire store of built-up rage, completely unrelated to her. I would hunch in my seat, weaving an elaborate fantasy of torturing, raping, and murdering her. Someone would say something seemingly innocuous, and my blood would choke as it boiled. I would feel as if I were drowning in a sea of red; I would try to stay on the surface, but wave after would submerge me. I had not known anger like this since my adolescence, my childhood -- the sort of rage that comes when you are accused of something you haven't done, or when a repulsive stranger is running his hands over your body. It was a child's anger, uncontainable, overwhelming. It was all I knew. I swallowed and tried to hold it back, but my heart would be racing and it would take everything not to crush the wineglass in my hand, to feel shards of glass bristling out of my flesh, or throw it against the wall and watch the pieces rain down. I practically panted with the effort of holding back, and though I never did what I wanted to do -- mostly because I would suddenly have a clear and terrifying memory of my schizophrenic aunt, who when I was a child would throw dishes against the wall during dinner in an attack of rage and paranoia -- I did derail a few social occasions with the anger I couldn't stop from spilling over. It shamed me, this impotent rage, this impatience with the people around me -- their little habits, which I had previously barely noticed, now irritated me so much I wanted to claw their faces until they bled. How do you admit such monstrous thoughts, even to yourself? But that was the severity of it. Something that might once have been a minor irritation, a fly buzzing in another room of the house, was now nails running down a chalkboard next to my ear.

[...]

How different is one person's tale of depression from another's? Is it often only the same story? Writing this essay, I was afraid to read the work of other people who had written in detail about their depressions -- I worried that not would the story be the same, but we would have somehow found the same language to describe it. The same phrases, the same words. How many ways are there to examine this litany of inertia, anxiety, anger and detachment? To describe a mental landscape from which all pleasure has drained, leaving it like, I imagine, the surface of the moon, pitted and barren? How could an affliction that feels so personal and singular, and in many ways inexpressible, actually be shared by so many? Like those ads that appear from time to time in the newspaper, run by some university or research group: "Are you depressed?" and, following, some of the symptoms. You recognize yourself, but it seems as generic as those pamphlets in the doctor’s office asking if you are an alcoholic, and you are because you, too, have lied about your drinking, missed work because of it, drink because you are nervous in social situations, etc.

[...]

Depression often seems to be accompanied by a certain level of narcissism. Its sufferers are always telling you how they feel, always checking the barometer of their emotional weather. They issue reports on it as they would on a matter of national significance. When I talk to my depressed acquaintances, their unhappiness becomes a claim on my attention and concern. A simple “How are you?" will elicit a detailed report on the person's recent moods and emotional states. This is the world they have come to occupy, the one they are trapped inside, and for all they know it has taken on the dimensions of the physical world itself. There is no other news, no weather or wars in another hemisphere. When you are not depressed yourself, it is a difficult state to tolerate in another. There is no visible wound to bandage, no doctor's pronouncement of a terminal illness with which to sympathize. There is only the unspooling of the grey ribbon of their days. You want to order them to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, to take a good look around those around them who are less fortunate and yet still manage to notice the sun shining in the sky, the first tulips pushing out of the earth. [...]

Their voices on the phone, disembodied, are instant indicators of their emotional states. When they are depressed, the usual highs and lows of infliction, of life and curiosity and enthusiasm, are drained away. Sometimes they cry, and then they sound like children, inconsolable.

[...]

I have never taken an antidepressant, and thus cannot describe -- though the writer in me would like to -- the physical and emotional changes, the sway and lift, the swirling sparkling grainy patterns of behavior breaking apart and re-forming. I wonder what about me would change, and cannot imagine the world emerging from under the shadow of certain depressive behaviors -- the sun coming out and a crisp slant to the architecture, everything clearly delineated, unmuddied. What would it be like to be free of those burdens, how many more hours in the day would there suddenly be to learn something new? Would my thoughts stop rotating obsessively around the tracks and grooves worn into my mind? Would I suddenly be free of whatever it is that immobilizes me, tethers me firmly to the past? It is a short leash that extends only so far as I strain towards defining a new life for myself, my own life, away prom parental expectations and childhood experiences that redefine, over and over, all my relationships -- from the most casual conversation with the grocery clerk to the most intimate sexual entanglement -- so that it sometimes seems to me that our fate is to live out our lives replaying what hurt us, what was taken away from us or denied us when we were small, watchful, easily damaged creatures.

What has stopped me from trying antidepressants, at least as an experiment, is the fear, of course, that

It began there, in that time between childhood and adulthood. How I loathed my life, my newly adolescent self! It was the usual resume of teenage misery, unremarkable in the end. Everything around me seemed thick and woolly and static -- the unwavering street outside the window of our little house, with a torturous glimpse of the down town lights in the distance, like a mirage I would never reach. The pudgy flesh I was gaining from my secret food binges made me feel leaden and sluggish. The texture of my skin, the oil in my hair, my ugly, scratchy clothes -- everything felt wrong, repulsive. I often prayed I would die in my sleep, so I would not have to face another day at school as an outcast. [...]

But when I next open my eyes there would be the familiar grey light through the window, and the depression would descend like a blanket. If it was winter it would be dark, and I would go to the kitchen to eat breakfast next to my father before he headed out on yet another of his unsuccessful job searches. The linoleum cold beneath our feet, our silent, awkward chewing. I would look at the soft slices of bread on my plate, how they broke apart under the jab of my knife with its dab of butter no matter how carefully I tried to spread it, and rage would course through my body. Why couldn't I butter a piece of bread without it falling apart? Why couldn't I be perfect? I wanted to take the entire loaf of bread in my hands, smear it with butter and honey, smash it in my hands, and hurl it against the wall. Perhaps then my father would rise from the icy lake of his torment, his unhappy eyes would focus, and he would see me.

I thought of suicide constantly; what likely stopped me was the thought of the trouble I would get into from my parents if I tried and didn't succeed. In the meantime, every day was a small eternity to be endured. The light in my memory of this time seems always to be charcoal grey, or black. The air felt thick in my nostrils and throat, and the depression expanded to fill the days, weeks, and months with its massive, rolling fog.

I was twelve, or thirteen. Younger, even. Perhaps it went on for months, stopped for a while, then started again; perhaps it continued for years, with only days of remission in between. Why can't I remember? Time meant something different then, and what seemed like years might only have been months, or weeks. But I remember looking at a calendar on my bedroom wall on which I had crossed out the days with big ink Xs, flipping back through the months and realizing I had been depressed for most of the tear. The memory of this is murky, a swamp of mornings waking in darkness, fear throbbing in a tight knot in my chest, and then the long day ahead wrapped in grey cotton. This state was different from pain, or panic, which I had known earlier -- those emotions arrived, were experienced, then left like their brighter counterparts. You survived them, and they had an acuity that depression, in its muffling weight, lacked. When I was depressed I would have given anything for a sharp, precise emotion, even if it was only sadness. Depression had no edges and therefore no borders, no discernible beginning or end.

Doctors claim that serious depressions are often triggered by loss, or by an accumulation of losses. Perhaps I was mourning the loss of the time when we had been more or less happy, as families go, before my father became unemployed and retreated to the dark basement in shame, before my mother became increasingly hysterical and stalked through the house terrifying me with her unpredictable moods and preoccupations. Before the arrival of my sister, who sat curled up in the crook of my father's arm while I watched from a sullen distance, murdering her in my mind. Perhaps I anticipated the unrecoverable loss that lay ahead, the day when as a fourteen-year-old I would walk out the door of my parents' house and never look back.

And then it went away. Or, perhaps, the depression remained but there but there was little room for it. I left home and tumbled into one crisis after another -- drugs, prostitution, suicide attempts, sleeping on the streets. Depression was elbowed aside by the immediacy of fear, by the cartoon nausea of bad LSD trips and drug overdoses, by struggling daily to survive. In retrospect, perhaps all that behavior was a form of self-medication. It was still better than the cotton-packed days of depression, which I learned to quickly eradicate with a handful of pills, a cupful of methadone, several tricks turned in a row.

In my early to mid-twenties the fog thinned and then seemed to lift for good. When I woke, the clear day lay ahead. I could intellectually recall the fact that I had been depressed -- I restricted it to a period in my early adolescence -- but could no longer feel it viscerally. It was like recalling a migraine, a pinched nerve, the time when you were at the kitchen counter and the knife slipped and sliced your finger open. You could describe it in some detail afterwards, but the memory of the pain would be less than a shadow of itself. This is how the body heals, how the mind closes over pain like scar tissue over a wound. When people I knew complained about being depressed, I had to swallow my impatience with them. I thought that at least they should have the grace to keep it to themselves, since there was nothing so dispiriting as listening to people almost lovingly explain the topology of their depression. The relentlessness of it, the iron lid over all their days. At least if they were experiencing a particular crisis there was heightened feeling, and you could offer a shoulder to cry on, a suggestion for action that they had overlooked, even a solution to their problems. Depression was something that simply went on and on, and wore out everyone around the depressed person.

I would try to sympathize by saying that I, too, had gone through a period of depression in my early teens. But that was all it was in my memory: a bleak, sluggish period, a long time ago. I never ceased to be grateful for its departure, though. I did remember that it had seemed worse than the most piercing pain, and so even when there was turmoil in my life, and grief, I was glad that it didn't devolve into depression. I began to think of that bleak band of time before running away as unique to a teenager's changing hormones and my circumstances at home; I saw myself as safely beyond its reach.